On the Work of Sarah Kane.

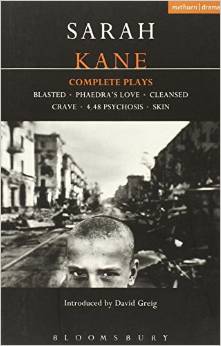

4.48 Psychosis: it’s the title of playwright Sarah Kane’s final play, currently being staged at the Royal Court Theatre (note – this article written in May 2001) and it refers to the hour of day when mental derangement is at its most extreme. Kane completed the play only a week before she hanged herself in hospital with her shoelaces and the play is, as she described it, ‘highly personal’. Inspired by Goethe’s novel, ‘The Sorrows of Young Werther’, the play culminates in the suicide of a young woman. Like Sylvia Plath, Sarah Kane clearly mined her own despair when writing and, whether intentionally or not, by her suicide has contributed to the myth of the tortured genius.

Sarah Kane killed herself in February 1999, aged 28. She shot to notoriety at age 23, with the production of her play ‘Blasted’, also at the Royal Court, which caused an instant tabloid scandal, condemned by ‘The Daily Mail’ as “a systematic trawl through the deepest pits of human degradation”. The way in which her work was seized upon by the hacks clearly had a lasting effect on Kane, who retained her dignity throughout the ordeal that followed, when, in the words of ‘Blasted’ director James Macdonald, “every editor and their dog put a journalist on the case looking for the author”.

Sarah Kane: my personal response

When I first heard the news of Kane’s death, I was profoundly shocked. I had never met her, but I was aware of her work and we had lived oddly parallel lives. Kane was 4 years younger than me, but had we been the same age, our paths would surely have crossed. In our teens, we were both members of Basildon Youth Theatre, which she must have joined, just as I left for Bristol University to study Drama. As I left Bristol Drama Department, Sarah Kane joined it. And later, whilst I studied for an MA creative writing in East Anglia, Kane was cutting her teeth on the MA in playwriting in Birmingham. But the parallels do not end there. Whilst I have not suffered from any serious depressive illness, I was, at the time of Kane’s death, embroiled in the subject of suicide, writing a novel about a writer, hounded by the media, who eventually succumbs to depression and takes her own life, securing for herself, incidentally, a place in literary history.

The myth of the tortured genius

The ‘tortured genius’ myth preoccupied me at that time. I’d spent several years questionning its validity. It began with Sappho in Ancient Greece, who leapt from a rock into the sea. In the eighteenth century there was Chatterton. He swallowed arsenic and so became a symbol for a whole generation of Romantic poets who measured their despair against his. After the publication of Goethe’s ‘Werther’ novel, about a young man who kills himself for love, suicide became positively fashionable. As Sarah Kane was clearly aware, ‘Werther’ inspired a whole spate of self-annihilations across Europe. Romantics believed that real geniuses had to live their lives in an intense and dramatic way. Like Coleridge, who effectively did himself away with opium. A. Alvarez, in his study of suicide ‘The Savage God’ writes, “At the high point of Romanticism, life itself was lived as though it were fiction and suicide became a literary act”. Only in the nineteenth century, with the demise of Romanticism, did the ideal of death by one’s own hand begin to dim.

But in our own age, the suicides continued apace. There was Hemingway, who shot himself; Virginia Woolf who plunged into the River Ouse; and Plath, of course, who gassed herself. Germaine Greer, in ‘Slip-Shod Sibyls’ has documented the lives of the many other, less famous, female poets who did themselves to death, including Anne Sexton, Ingrid Jonker, Eva Royston, Marina Tsvetaeva. Today, the Plath hysteria has not abated and with the 1998 publication of Ted Hughes’ ‘Birthday Letters’, Hughes’ death in 1999, and Faber’s publication this year of Plath’s diaries, there are no signs of the public interest abating.

Plath, like Kane, used her depression as subject matter for her writing. She mined her grief and gave it substance, penning lines that have continued to define the way we view the link between death and creativity. Plath wrote that dying is an art. In one of her final poems, ‘Edge’, she described a woman, perfected by death, wearing a smile of accomplishment. As if death itself, were some kind of achievement. Kane does not romanticise death, but she does reinforce, in her work, the link between death and the act of writing. A character in her play, ‘Crave’ says: “I write the truth and it kills me” and in interview, Kane said, in relation to ‘Blasted’, “There is an enormous amount of depression in the play because I felt an enormous amount of despair when writing it.” After Sarah Kane’s death, her agent and close friend Mel Kenyon commented, “I think she felt something … like existential despair which is what makes many artists tick.” This comment was immediately seized upon in a letter to the Guardian. Anthony Neilson wrote “Nobody in despair ‘ticks’ – and for Sarah Kane the clock has stopped. Truth didn’t kill her, lies did: the lies of worthlessness and futility whispered by an afflicted brain. They’re lies told to artists and check-out girls alike, but we canonise one and stigmatise the other.”

It is easy to understand Neilson’s frustration. If we repeat the idea that despair and art are intricately linked, are we not fuelling the Romantic oven? Are we not encouraging would-be artists to believe that only if we enter into the depths of our own misery will we produce an art that is real and worthy? Nobody wants to encourage suicide. It’s a horrific waste and a growing social problem. A recent survey revealed that one in eight young people has considered or attempted suicide. Suicide is the biggest killer of young men after road accidents: there has been a 71% increase in suicide by young men in the last 10 years. At Edinburgh University, five students (four of them women) have killed themselves in the last 2 years.

Contemporary views on creativity and despair

The question we must ask is, did Kenyon have a point? Are writers and artists more prone to depression and if so, are they drawn into depression by their work, or is it, conversely it is the work that causes the despair? Novelist Louise Doughty was theatre critic for the Mail on Sunday when ‘Blasted’ was performed at the Royal Court. She was the play’s only defender among the national theatre critics. “I also saw the opening of Phaedra at the Gate and Cleansed at the Royal Court,” she says, “and I pleaded publicly with everyone to give the kid a break and leave her alone for a bit.” Doughty, also, has suffered from depression. “I’ve found it very intimately connected to my creative writing but in a way which is much more subtle than people might think. When I’m depressed I can’t write – I can’t do anything other than get through the day. When I’m euphoric it’s not possible to write either, it’s like having ants in your pants. But my best work is often done in the transition phase between depression and euphoria.”

This is a view echoed by novelist Anna Davis. “I write at my best when I am feeling calm and level-headed. If I’m either depressed on the one hand or exuberant on the other, I can’t settle down, concentrate and focus properly. I think there’s something intrinsically unhealthy about the idea that creativity is in some sense fuelled by depression.” These writers’ views contradict the myth. Whilst both have experienced depression of some kind, neither has felt the need to purge themselves of that feeling at the time by writing. However, the more one talks to writers, the more one becomes aware that depression is something that most are very keen to talk about; as if it’s a common language.

Liz Jensen is a novelist who admires writers who tackle dark subject matter, but avoids this herself. She writes to “cheer myself up”. Yet she believes that writers are indeed prone to gloom, “because we’re doing something emotionally dangerous, which is to put our souls on the line. When you’re engaged in a feat of the imagination, you are dredging up something quite deep within yourself. Perhaps feeling things acutely is the price you pay for going that far into your subconscious. It’s the entry fee.” Yet Jensen, like the other novelists I spoke to, also spoke of the up-side of writing: “For every low, there’s an incredible high. When it’s going well, you’re soaring – and there’s nothing like it. There’s a definite payoff.” Davis, equally, seems to refute the myth of the tragic writer. “I know that for many people there is indeed a link between dissatisfaction, despair and the creative process – but not for me. I think you’d have to be pretty neurotic to really buy into that idea – I’d hate to think that you had to be a suicidal neurotic in order to be truly great.”

It’s a view that Germaine Greer and Anthony Neilson alike will doubtless be pleased to hear. Greer fears that female writers who “fail to flay themselves alive…will be called minor”, yet surely now, we are beginning to move beyond that idea. Surely we must see that whilst there may be some link between depression and creativity, it does not follow that greatness and self-destruction are inextricably linked. Doughty believes that it was not Sarah Kane’s work that made her commit suicide. “If her career contributed at all,” she says, “it was the success that tipped her over the edge, the sudden attention and the disgusting sensationalism of the tabloid press.”

Wedding Rondeau: musing on a serious literary life

Wedding Rondeau: musing on a serious literary life

What a profound article Jacqui. I don’t know how I missed this in the past, but I’m moved and fascinated to read it now. All I can add from my own experience is that writing sends me deep inside myself in a way that feels cleansing and soothing….. As thought sub conscious elements are set free….

Thanks for your comment Voula. This one was on my original blog, a long time ago, so only just reposted. So glad that you found it interesting and thank you for your comment. I agree, for me there is nothing destructive about the process; I feel more psychologically healthy and whole when I do write.